A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography at C/O Berlin

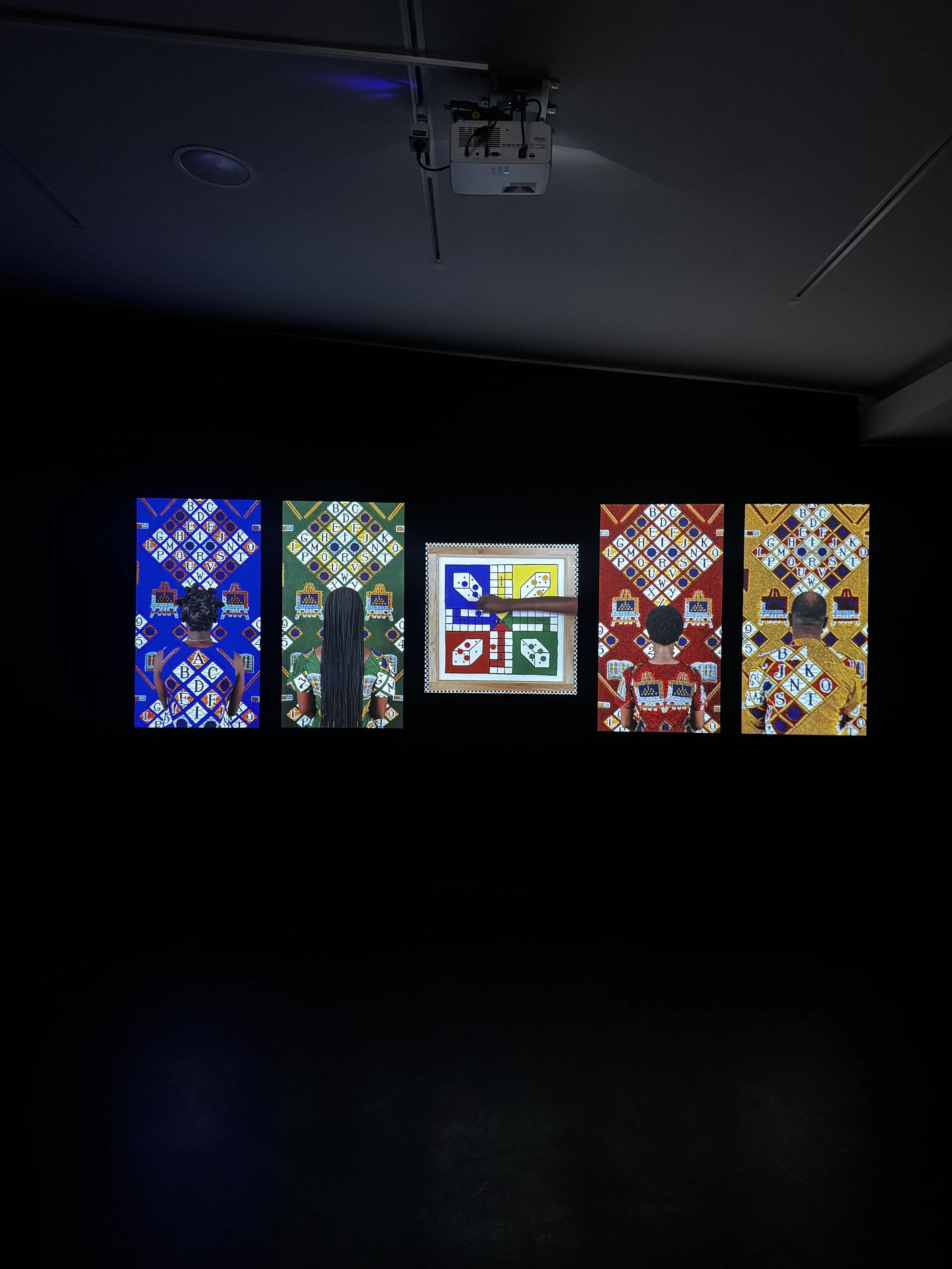

With A World in Common, C/O Berlin presents one of the most ambitious surveys of contemporary African photography shown in Germany in recent years. On view from 1 February to 8 May 2025 at its historic site on the famous C/O Berlin, the exhibition unfolds as a nuanced meditation on a continent far too often reduced to singular narratives. Here Africa appears instead as a constellation of voices, aesthetics and political positions that resist simplification.

The exhibition is structured into three thematic chapters, allowing visitors to move between different modes of image making and social imagination. This curatorial approach gives the works space to breathe while carefully tracing shared concerns around identity, ecology, history and self representation. The project arrives in Berlin after an earlier presentation at Tate, yet the transformation within the architecture of C/O Berlin is radical. Where the London display leaned toward monumental spatial gestures, the Berlin version feels more intimate and slower. Individual positions now emerge with greater clarity and emotional weight.

The exhibition also reflects on the broader infrastructure shaping cultural production on the continent today. The Siemens Stiftung appears as a key institutional partner, highlighting its long term engagement in African contexts through projects in water purification, cyber security and digital education initiatives such as African Women Can Code. These references are not presented as corporate decoration but as indicators of how technological and social frameworks intersect with artistic practice. Alongside Siemens Stiftung, the support of Wolfgang Tillmans signals how artistic patronage continues to influence which narratives gain international visibility.

What distinguishes the Berlin presentation is how clearly individual positions now read against this institutional backdrop. The sensitive and decisive curatorial reconstruction of Cale Garrido, after the first curation of british-Ghanaian curator Osei Bonsu at Tate Modern in London. Rather than forcing thematic coherence, Cale Garrido allows productive friction to remain visible. The result is an exhibition that does not smooth over contradiction but embraces it as a condition of contemporary image making in the diaspora and from the continent itself.

The exhibition brings together a broad constellation of artists working across the African continent and its diasporas, including Délio Jasse, Keyezua, Mário Macilau, Aïda Muluneh, and Zanele Muholi, among others. Together they form a multilayered visual geography that resists any single reading of the continent.

Particularly compelling is the work of Délio Jasse, born in Luanda and based in Lisbon. His practice is rooted in archival intervention. By reworking colonial era documents and photographs through processes of layering, staining and reprinting, Jasse exposes the bureaucratic violence embedded in official histories. His images feel like wounded records, fragile and insistent at once, revealing how memory in post colonial Angola remains fractured yet defiantly present.

Edson Chagas works with photography as an act of quiet resistance against spectacle. Born in Luanda, Angola, and based between Africa and Europe, Chagas is known for his series of discarded objects staged in urban landscapes. By placing abandoned furniture and everyday remnants into carefully composed scenes, he exposes the overlooked poetry of the post colonial city and the lingering traces of consumer culture, memory and displacement.

For audiences attuned to Afropean practices, A World in Common offers an especially fertile ground. While the exhibition is explicitly dedicated to the African continent, its reverberations across Europe are unmistakable. Many of the questions raised resonate deeply with Afropean realities. Who controls the archive. Who frames history. Who decides what becomes visible on the global stage. The dialogue between African and Afropean positions here feels implicit rather than forced, grounded in shared political urgency rather than formal resemblance. Together, all shown positions exemplify the variety of the continent and how contemporary African photography moves far beyond documentary convention.

A particularly strong focus lies on emerging talents on the second floor of C/O Berlin in another but still suitable exhibition, and among the most compelling discoveries is Silvia Rosi and Sam Youkilis, whose work appears expanded here within the context of the C/O Berlin younger and emerging artists programme.

Rosi’s practice moves between documentary and constructed image, often exploring the fragile thresholds between visibility and disappearance. Her photographs draw attention to bodies and spaces that remain marginal within dominant visual regimes. At C/O Berlin, her series unfolds with a new precision. The proximity of the rooms sharpens the political tension within her images and allows the quiet strength of her compositions to surface fully. Rosi’s contribution exemplifies how emerging afrodiasporic perspectives can enter into meaningful dialogue with African photographic practices without collapsing their distinct histories.

As an international platform, C/O Berlin once more demonstrates its ability to host internationally relevant debates while nurturing emerging voices. The exhibitions do not claim to represent Africa, but stages encounters with artists who actively reshape how both, younger and older Africa can be seen and understood. In doing so, it opens a space where Afropean viewers in particular may recognise echoes of their own negotiations between continents, archives and futures yet to be written.